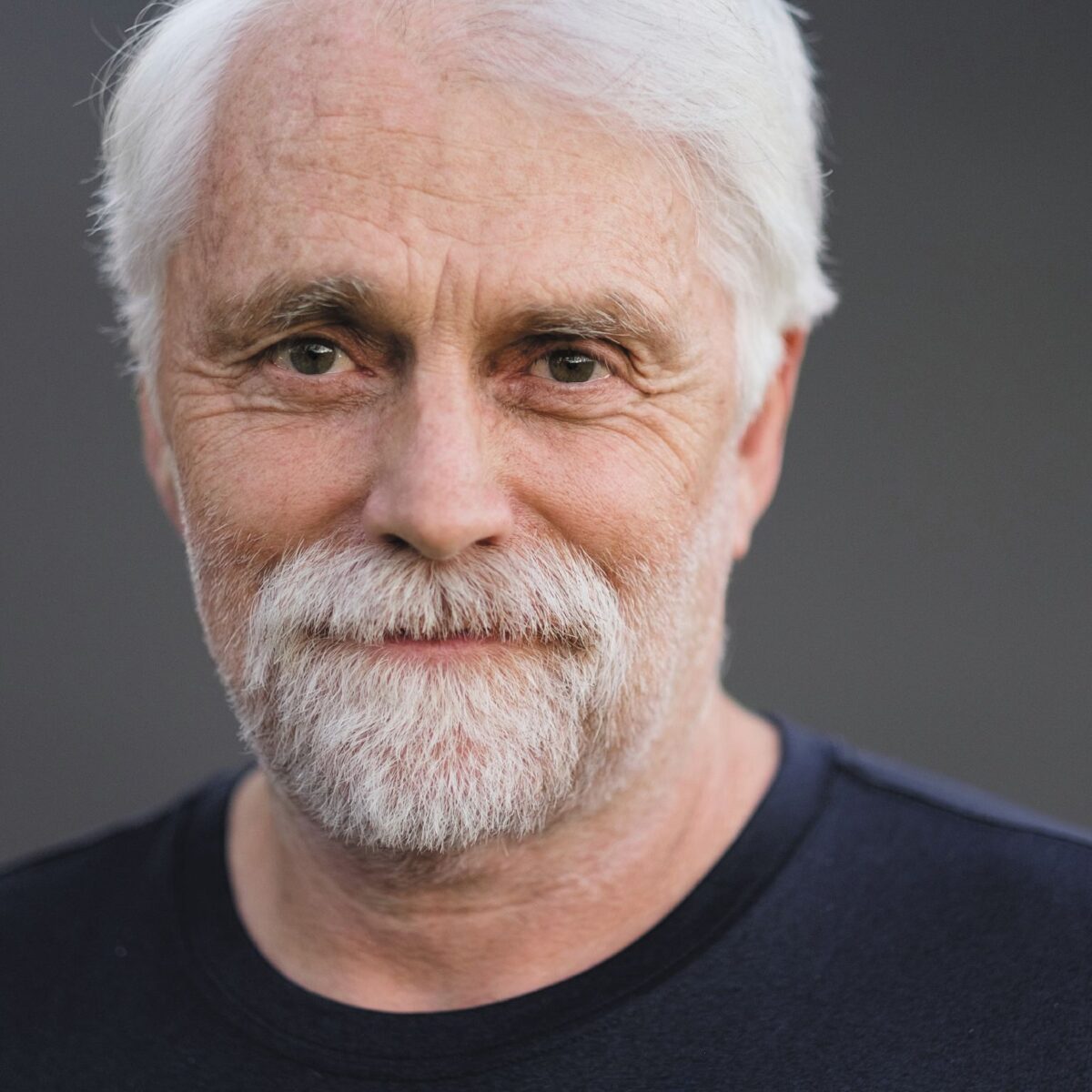

Philosophers often sidestep the issue of violence, refusing to tackle it head-on. One philosopher who has never refused the challenge is Professor Gordon Marino, who as well as being a professional philosopher was once a professional boxer and boxing coach. We spoke to him about the crossroad between philosophy and combat sports.

Professor Gordon Marino had a tough youth. Speaking to the professor it is clear that he admired his father, telling of his upward mobility despite his Italian immigrant background. Yet, the relationship wasn’t straightforward. Raised with expectations to achieve well in sports, Gordon played American football. His family said he couldn’t do boxing, but his grandfather pulled him aside and said why not try it. It seemed, says Marino, “the basis of all competition.” He was enamoured of Floyd Patterson’s career, and wrote to him and ringed him up. So started the fistic love affair.

Professor Marino signed a pro contract in 1973 in New York, but quickly realised he was being out-boxed, being put in with top contenders and “having the crap beat out of me, not learning anything.” So Marino packed up. This, however, influenced his later coaching. He was surrounded by people when he was boxing, but nobody was able to teach him anything. This leads to bad muscle memory, and what he was told was: “if you can stay in there with these guys, that’s big!” But, adds Marino, you don’t learn the technique when you are sparring someone who is more experienced. A lot of experience is needed to become a good coach, but his career as a boxer never materialised.

The ability to fight, at least in males, makes you feel more at home in your skin – even if it is imaged and you think you are bad-ass but you are not. I’m a pluralist when it comes to this, but it can make people feel less aggressive and less defensive. It serves that function. I also think that, psychologically and historically, human beings fail to recognise the sadistic impulses we have.

Later in life, Marino would work as a boxing writer for The Wall Street Journal, and one of his hallmarks was asking fighters what their signature move is. He was surprised because they always had one at the top of their minds. They didn’t have to think! In his estimation, the best piece he ever wrote traced Floyd Mayweather’s technique to Grand Rapids, Michigan, but Mayweather suspected Marino was working for his opponent, so he started throwing Marino off guard, saying one should pivot off the wrong foot, and adding all sorts of embellished stories!

PHILOSOPHY AND BOXING

As a philosopher, now Emeritus Professor at St Olof’s College, Marino has published a vast body of work on Kierkegaard and Existentialism in particular. I ask him how he unities his philosophical work with his love for combat. How does he, as a philosopher, answer the question of why we are drawn to fights? The professor has mixed feelings. “The ability to fight, at least in males, makes you feel more at home in your skin – even if it is imaged and you think you are bad-ass but you are not. I’m a pluralist when it comes to this, but it can make people feel less aggressive and less defensive. It serves that function. I also think that, psychologically and historically, human beings fail to recognise the sadistic impulses we have. Look at Ukraine! Just plain f-ing sadism!” The professor speaks about Guantanamo, the detention camp located within the US naval base in Cuba, where they blocked up the windows so the inmates can’t see the ocean. “You know what I mean? I think sadism is something we don’t account for sometimes. It is there – read Nietzsche! He’s the man to read. He said: ’To see others suffer does one good, to make others suffer even more: this is a hard saying but an ancient, mighty, human, all-too-human principle [….] Without cruelty there is no festival.’ I think the MMA stuff, YouTube street fights… we are infinitely fascinated by this stuff. Even in politics, we say ‘he’s a fighter!’ In the US, if you are not considered a fighter, you cannot get elected.”

You deal with anxiety and anger, which are fundamental impediments to being a good human being, and one doesn’t get much practise at this in our society. If you are anxious, they just give you a pill. They are protected from anxiety. Boxing is a workshop for those emotions.

Philosophy itself, the Professor continues, is a very antagonistic sport. You have to try to destabilise your interlocutor, “instead of getting punched on the nose, you work on a paper for 6 months and someone punches a hole in your reasoning and that’s it!.” This goes back to the Greeks as well, where philosophy was considered an intellectual wrestling match. This is no accident, as most philosophers also practised martial arts, especially wrestling. “Philosophy can be very aggressive.”

Do approaches to violence and combat sports differ depending on the philosophical school one subscribes to, I ask. For example, working within the existentialist tradition, does Professor Marino see a particular view of violence merge, as opposed to ancient philosophy? Definitely, he thinks. If you want to teach children to be good people, as an example, you need to practise. Just as in boxing. “You deal with anxiety and anger, which are fundamental impediments to being a good human being, and one doesn’t get much practise at this in our society. If you are anxious, they just give you a pill. They are protected from anxiety. Boxing is a workshop for those emotions. You learn to take a hit as well. If you want to be a good person, you will have to know how to take hits in life! Boxing teaches you about that – not that physical and moral courage are the same! – but I would tend to trust a person who has physical courage in a moral situation versus someone who didn’t. The Stoic view, or Aristotelian even, where you get to practice with emotions through physical exercise is important. From a social point of view as well, something which I learned through friendship with George Foreman, is that as a devout Christian (and a killer puncher) I saw a paradox between his tremendous power and deep deep faith. I asked him about this and he said: one of the reasons he opened a gym is because so many kids don’t get any affirmation in life. They come to the gym and their fathers are there, and they build a community.” In America, explains Marino, if you grow up in a dysfunctional environment and get pissed off, go to school and get into trouble, nobody says a good thing to you, once you enter a gym you find that respect and affirmation.

THE AESTHETICS OF BOXING

We end by discussing a perplexing issue: that violence can be beautiful. It’s a mystery, says Marino. Giving a talk at a law school, the professor thought he would speak about the meaning of commitment. He used clips of Frazier vs Ali to illustrate the point to the students, and what he saw was the expression of students thinking he was mad! This goes back to Plato in the Republic:

The story is, that Leontius, the son of Aglaion, coming up one day from the Piraeus, under the north wall on the outside, observed some dead bodies lying on the ground at the place of execution. He felt a desire to see them, and also a dread and abhorrence of them; for a time he struggled and covered his eyes, but at length the desire got the better of him; and forcing them open, he ran up to the dead bodies, saying, Look, ye wretches, take your fill of the fair sight.

There is a mystery. We want to watch the violent, the macabre, the terrifying, and the sublime, often with excitement. But we are also aware that we are feasting our eyes on something that rightly fills us with dread.

Lyssna på det senaste avsnittet av Fighterpodden!

Kommentarer