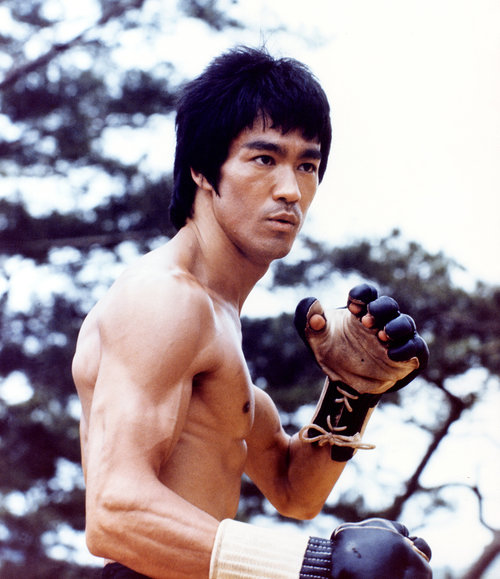

Bruce Lee was born on November 27, 1940, and died on July 20, 1973 (he would have celebrated his 82nd birthday last week). Since his passing, much has been said about his system, Jeet Kune Do, and its philosophical roots. They have all pointed to the same Taoist and Zen Buddhist sources that already lie behind other martial arts philosophies. But how Eastern is Lee’s system?

During much of the 20th century, the Far East was still exotic and foreign to many Westerners. Like the brain, the planet seemed divided into two hemispheres. The left half stood for logic and reductionist analysis, and the right for intuition and holistic perception. Grossly simplified and, of course, from a Western perspective: the West stood for advanced technology and rationality; the East stood for ancient wisdom and mysticism.

During the 20th century, this gap was increasingly bridged. Martial arts legend Bruce Lee (born November 27, 1940, in Chinatown, San Francisco, California, died July 20, 1973, in Hong Kong) was essential to that development. Eventually, he would lay the foundation for a new way of portraying Asian people in American and European cinema.

When Lee appeared on the big screen, he still personified the exotic and romanticized image of the Far East. His movements were almost supernaturally quick, while Lee’s speech was full of mystical wisdom. His classic quotes include ”Finger pointing at the moon” and ”Be water, my friend”. These are quotations that have direct parallels in Zen Buddhist and Taoist sources.

But where had Bruce Lee encountered them?

The Western ”Zen Boom”

Today, Eastern-tinged expressions are well integrated into the Western consciousness, but when Bruce Lee uttered them, they were still unusual and esoteric. But of course, these ideas were not new in the West even then. In 1959, when Lee returned to the United States as an 18-year-old, the Beatnik movement had already flirted with Buddhism for a few years. When Lee appeared publicly, the hippie culture with its Hindu influences was blooming.

Even earlier, people such as theosophist Helena P. Blavatsky (1831-1891), Ramakrishna disciple Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), psychologist Carl Jung (1875-1961), and author Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) had spread Eastern concepts and teachings in the West. During the first half of the 20th century, mainly academics, intellectuals or people interested in the occult were familiar with Oriental philosophy, which would change with the so-called ”zen boom” that took off a few years after the end of the Second World War.

The Japanese writer DT Suzuki then taught in American universities and influenced the protagonists of the Beatnik movement, such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. At the same time, the Christian monk Thomas Merton (1915-1968) highlighted the remarkable similarities between Zen and contemplative monastic life. Eventually, even ordinary people began to experience their own ”zen boom” via radio and television.

A man with a Western background was behind a large part of this development: Alan Watts, one of Bruce Lee’s absolute favourite authors.

The Rock Star Philosopher – Alan Watts (1915-1973)

Like Bruce Lee, British-born Alan Watts was crucial in bridging the gap between East and West. As early as 1936, Watts published his first book, ”The Spirit of Zen”, heavily influenced by DT Suzuki. During the fifties, he began his work with a series of radio and TV programs, which understandably presented and popularized Eastern philosophy to a broad audience. In addition, they died within the same month in 1973. Watts developed his worldview, becoming increasingly apparent in his books and lectures, which can be described as a mixture of Hinduism, Zen, Taoism, pantheism and mystical Christianity. Prominent is the Hindu-tinged idea that the entire cosmos is a spectacle in which a single consciousness takes on infinite roles. Through an egoless state of Zen, fully present in the present, man can see through the illusion of existing as a limited and separate entity. In this way, one can instinctively act by following nature, unaffected by personal thoughts and beliefs.

Something of a rebel and rock star character, Watts was often criticized for spreading his own ”westernized” version of the Eastern religions. After Watts’s death, he was forgotten for a while. Still, in recent years Watt’s philosophy has begun to be noticed again because his program and many recorded lectures have found their way onto the internet.

A little trouble in Hong Kong

Hong Kong in the 1950s was a growing industrial melting pot of British and Chinese culture. In an aggressive and growing metropolitan environment, there was less and less room for traditional Chinese values. Bruce Lee received his first martial arts training in Hong Kong (he trained under Yip Man), but there is no evidence that he was interested in the philosophical aspect of martial arts. On the contrary, the reason for his leaving was countless cases of fights and violent behaviour. Bruce was in trouble with the law, fearing rival gangs were after him. When Lee arrived in the United States in 1959, he gradually began his philosophical studies at the University of Washington. The American ”zen boom” was then in full bloom, and Alan Watts was undeniably one of the leading exponents of it. There is no doubt that Watt’s Eastern-tinged philosophy came to influence the design of Jeet Kune Do. Among other things, via Lee’s wife Linda Lee Cadwell, it is well known that Watts was among the authors the martial arts star read most often. Thanks to her, we know, for example, how Lee, after his back injury in 1970, spent his six-month rehabilitation period studying literature by, among others, Watts.

”Non-action” – Wuwei

Because he preferred the mystical veins of religion, Watts was fascinated by the paradoxes often encountered in Eastern philosophy. The Heart Sutra of Buddhism is a perfect example of this:

”Emptiness is form; form is emptiness”.

One of the points of such contradictory statements is to free consciousness from the dualism through which the human mind filters reality. According to Watts’ Eastern-colored worldview, they thus counteract the illusion of existing as a separate ”ego in a bag of skin”. Beyond that illusion awaits the realization that what we call individuals is only ’Brahman’, observing itself from various perspectives. This thought affected Lee deeply.

Lee often described Jeet Kune Do with paradoxes, such as ”the art of fighting without fighting” or the ”styleless style”. The content of these paradoxes belongs to the type of Taoist ”wu wei” philosophy popularized by Watts. ”Wu Wei” literally means ”non-action”.

Nevertheless, it is not pure passivity. Instead, wuwei can best be described as a paradoxical action through non-action. With a pure mind, empty of self-will, one lets the Tao (Tao or Dao means ”way”, but there are several other broader explanations – ”method”, ”doctrine”, cosmic law and so on) rule and act spontaneously only when it is necessary.

”To be like water.”

Here we find the origin of the analogy with water – an element that, in its passive stillness, nevertheless flows naturally according to the Tao. Laozi, the supposed author of Taoism’s excellent record Tao te Ching, is full of water symbolism that gives birth to a quote like ”Be water, my friend”. Watts was also fond of water symbolism. An excerpt from his famous ”The Way of Zen” perfectly describes the water element’s ”action through non-action”:

”As cloudy water is best cleared by being left alone, one can say that he who sits quietly and still, doing nothing at all, is doing the best possible for a world in chaos.”

One of the basic ideas of Jeet Kune Do is ”maximum result with minimum effort”, which is not far from the water symbolism of Taoism. One can compare this with a quote from Bruce Lee himself:

”The big mistake is to expect greater results with greater commitment. You should not think about whether you will win or lose. Instead, let nature take its course, and your skills will show themselves at the right moment.”

Other influences from Zen

As a representative of the ’zen boom’ of the fifties, Watt’s philosophical work naturally revolved primarily around Zen Buddhism. Zen is intimately connected with martial arts.

According to legend, this vein of Mahayana Buddhism was created by the monk Bodhidharma at the Shaolin Temple, which today is best known for its martial arts techniques. Legend has it that when Bodhidharma first reached the temple in the late fourth century. However, the physical health of the monks was in poor condition. Distressed by this, he is said to have meditated for nine years to find a solution to the problem. The result is said to have been the basis of the ”kungfu” (in the Western world, the word kungfu (功夫), or ”skill through hard work”, is often mistakenly used as an expression of Chinese martial arts. A more appropriate term for this is wushu, martial art) which still lives today.

Zen Buddhism, which today is mainly associated with Japan, is called in its original Chinese form ”chan” (originally from the Sanskrit word ”dhyāna”, which roughly means ”meditation”).

Deeply influenced by Taoism, Zen Buddhism is characterized by the same absolute presence in the present. The idea is to act freely and correctly without the preconceived notions of the mind standing in the way, which is where we can find the origin of the quote, ”Finger pointing at the Moon”.

In the Shurangama Sutra, a core text of Zen Buddhism, the Buddha uses the exact simile to distinguish between the concepts of the teachings and the wordless truth to which the teachings try to point. Doctrine is just finger-pointing to the moon/truth. Anyone who only stares at the finger misses what is being pointed out. Even worse, such a person tends to confuse the finger/teaching with the conceptually elusive truth being pointed out. In this way, all literal interpretations and fundamentalism are born. Of course, this also applies to martial arts philosophies, which Lee often found too rigid.

Alan Watts often used the Buddhist simile of dharma, the teaching, as the raft helping one across a river. Once you are over, you don’t continue to drag the raft with you on land, which thought Lee transferred directly to his martial arts philosophy: Jeet Kune Do just a name, a boat that takes one over. Once you are over, you should let it go and not drag it on your back.

The Modern Mystic – Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986)

The hippie culture emerged about a decade after the ”zen boom” of the fifties. Where Buddhism had primarily inspired the Beatnik movement, the ”flower children” of the sixties were drawn to Hinduism. The members of The Beatles practised transcendental meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, while Indian gurus such as Meher Baba and Neem Karoli Baba also attracted followers in the West.

Apart from Watts, the person who most influenced Bruce Lee partly belonged to this crowd, namely the Indian philosopher and mystic Jiddu Krishnamurti. However, his guru status was wholly involuntary and something that troubled him.

Unlike Watts, Krishnamurti came from an Eastern culture. As his life unfolded, his spiritual upbringing was to be through a Western system. As a boy, he was declared by the theosophical movement as a new Messiah. Soon a cult was formed around him, and at thirty-four, Krishnamurti renounced the role in front of 3,000 followers and then went his own way. He was critical of all forms of authoritarian and organized teachings for the rest of his life. His message: It is the right and duty of every individual to find his way of approaching the truth. No single movement or authority has all the answers because ”Truth is a kingdom without roads.”

The parallels are clear to Jeet Kune Do. Lee’s ”styleless style” goes as far as to say that there is no other authority – no fixed system – than what the present moment dictates.

Krishnamurti’s influence on Jeet Kune Do runs so deep that the words ”religion” and ”martial arts” in the two men’s philosophies are almost interchangeable. For example, one of Lee’s most widespread and famous quotes perfectly describes Jeet Kune Do and Krishnamurti’s philosophy.

”Embrace what is useful, reject what is not, and add what is your own.”

When East meets West

Perhaps the philosophical basis of Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do can be summarised as distinctly Eastern – mainly Buddhist and Taoist. However, many of the instilled ideas first passed through Western minds before being picked up and adopted by Lee.

After Lee’s death, the breadth of his library was revealed. Most of it consisted of Western writers such as Descartes, Jung, Russell, Plato, Spinoza, Hume, Goethe, Campbell and even the 13th-century Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas.

However, no writings on Jeet Kune Do were published during Lee’s lifetime. Only after his death came the book Tao of Jeet Kune Do, a compilation of Lee’s thoughts and notes. One of the reasons why Lee hesitated to release his beliefs was precisely the fear that they would turn into rafts that people dragged on their backs – fingers that people stared at, only to miss the moon.

Lee feared that his followers would interpret the system dogmatically instead of seeing it as an organic approach to martial arts. In this way, Jeet Kune Do is not a fixed system but something that, like reality (or like the Tao, if you like), flows, lives and changes. There are no fixed rules. Instead, one of the foundations of the system is a principle that is both Taoist and ”Krishnamurtish” at the same time:

To have ”no way as a way”.

Lyssna på det senaste avsnittet av Fighterpodden!

Kommentarer